Should CEOs discuss software defects?

You wake up, and probably check your smartphone immediately. Chances are you already have smart devices at home; like light bulbs, you turn on and off from the same smartphone. You often check traffic and estimated time arrivals of your commute by using an app or online service. Software aids plenty of operations while you drive, like braking and accelerating (even if you’re not aware). No matter the job, work has to cross over digital boundaries. Also, to see your friends or family, a piece of software might be in the midst. Much of the time, consciously or not, our lives develop over software grounds.

Figure 1. Software is eating the world by Gerd Leonhard. Source flickr

Corporations have brought us software. They now depend heavily on coding for sustainability and to keep competitiveness. Organizations of all sorts are becoming more like tech companies focused on specific services. The shift is more clear in some industries like banking: no bank would survive without information technology. IT spending keeps growing across the globe. You probably have read that “software is eating the world”, a sentence by Marc Andreessen —Netscape founder and venture capitalist—, written in an op-ed back in 2011. It has already eaten nearly everything.

Why bugs and vulnerabilities should be CEO’s top of mind

With software so pervasively present, corporations should consider putting more attention on theirs at a strategic level. A recent Harvard Business Review piece written by Nicholas Bowen suggests that fixing software defects should be a CEO’s priority. We can’t agree more. Some global cases support this view.

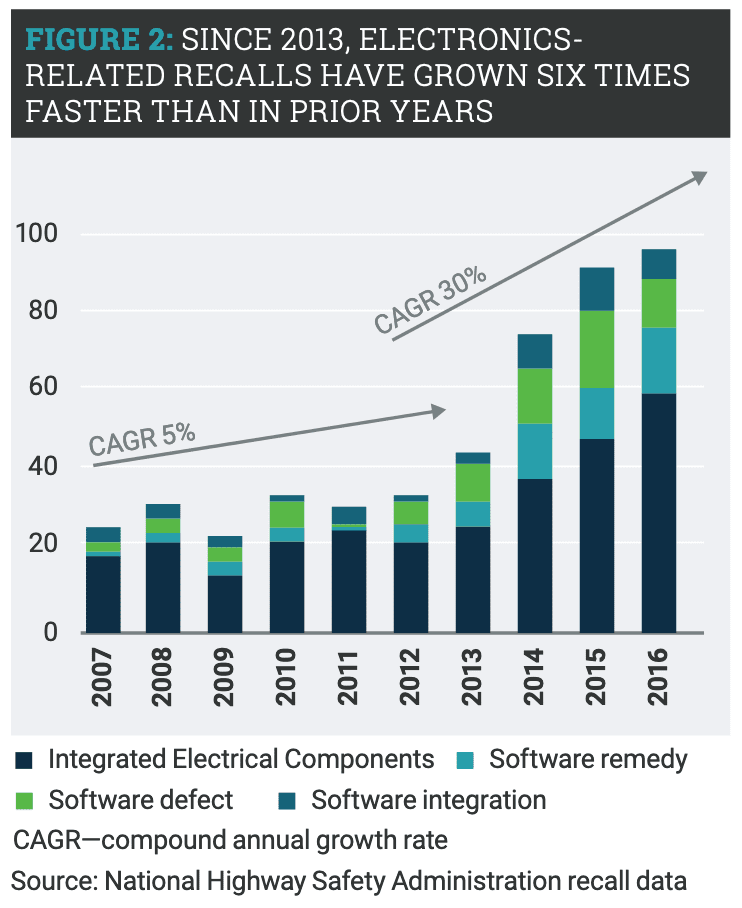

In 2003, there was a massive blackout in North America, covering several states in the US and Canada. More than 50 million people were left with no electricity for two days or more. An investigation found a race condition was present in a Unix-based system (XA/21), which stalled a critical process. Last year, a software defect caused two fatal incidents in two brand-new Boeing 737 MAX. The press coverage was massive. The bug affected a critical alarm for captains, inhibiting timely maneuvering. Business Insider confirmed the airplane manufacturer knew the defect for around a year. Bowen’s article draws upon two similar cases. One tells about how Toyota settled a lawsuit in USD 1.1 billion by a sudden acceleration problem in one of its models, which caused deaths. Again, it was a software bug. In line with this type of defect, the National Highway Safety Administration reported that only one car manufacturer recalled 80.000 vehicles in 2016 due to software defects. The other case is Microsoft, which in the nineties experienced spectacular growth, so much that the share of software defects and vulnerabilities among operative systems around those years was higher for Windows. Do you remember the “blue screen”?

How much do other of these escapes —defects and weaknesses— cost to corporations? More importantly, how much do they cost to society? Vulnerabilities are rising and probably will keep growing. Organizations can find a competitive advantage in paying more attention to software quality, deployment, functionality, and security. Making sure testing efforts are performed with high standards should be more prominent in C-level discussions about product and service development and delivery.

What can be done about this?

Bowen suggests that asking simple questions can cause a turnaround by making an organization proactive with software quality management. CEOs could ask, “what criteria was used to determine when the product was ready to be shipped?” attempting to capture attention to quality processes. Moreover, executives should ask for the defect status months after releasing a software product, seeking to prevent significant size events, like car or airplane crashes. In the case of an incident, executives could ask, “how did the software get released with that type of bug?”

These questions are important but aren’t enough. An effective quality management system should be in place, and not every CEO is in a position to assess that. At Fluid Attacks, we have blended robust technology, automation, and the best hacking skills in the market to address security quality issues in the whole software development lifecycle. Our hacking tests covers from static code analysis to attacks (controlled, of course) to production environments. We centralize every security hole in our Attack Surface Manager (ASM). And along with processes and technology, our Criteria act as unifying chain; a criteria to classify findings so customers can quickly identify and decide where to start fixing defects. We also test the effectiveness of fixes and break the build every time software doesn’t follow those rules.

Will you ask those questions to your team? We can help by giving them to you without even asking. Everything would be available at our ASM, covering from very technical to strategic levels. Bowens propose a simple 2x2 matrix to assess how an organization is performing based on quality awareness and response to bugs. Fluid Attacks can help you moving towards the upper-right.

But, do not just ask for bug reports.

In emergency rooms, medical staff has to make quick decisions under uncertainty, with tight time frames and sometimes without clear how-to’s to keep people alive in extreme conditions. Some researchers have found a positive correlation between the number of mistakes made by teams and their results. This is counterintuitive: more mistakes, better results. Best-performing groups show a riskier behavior (hence the errors), but these teams also share more among themselves about those risks and mistakes. In turn, they find better results from these interactions, allowing more experimentation, and achieving incremental improvements. Why? Psychological safety.

Psychological safety, coined by professor Amy Edmonson, is a state where people aren’t afraid to speak up when needed and to accept their mistakes. Teams feel psychologically safe when they expect no retaliation from sharing uncomfortable yet essential matters to their peers and managers, like pointing out something that might endanger a project just before it is launched. Trust and openness are key.

Bowen’s related his own experience at IBM when software defects were harming. A VP was commissioned to revert the trend and he had a motto: “be forthright, and I’ll be forthcoming”. To make software defects and security weaknesses chief for high leadership, companies have to create a safe environment so technical teams aren’t hesitant to reveal what is or might be wrong. If people think speaking out would threaten them, they will be dangerously silent. Some incidents, like Boeing’s, seem to reveal an effort to cover things up. In Volkswagen’s gas emission scandal, people who bravely spoke up were fired.