Why is security always excessive until it’s not enough?

On June 28, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) published a report explaining why cyber insurance spurs ransomware attacks. After its publication, several blogs emerged summarizing or detailing the problem (I recommend ZDNet , PCrisk, TechTimes and Security Intelligence articles). This blog post is not intended to summarize the RUSI report. Instead, it will use it to describe and explain the relationship between cybersecurity insurance and the rise of ransomware.

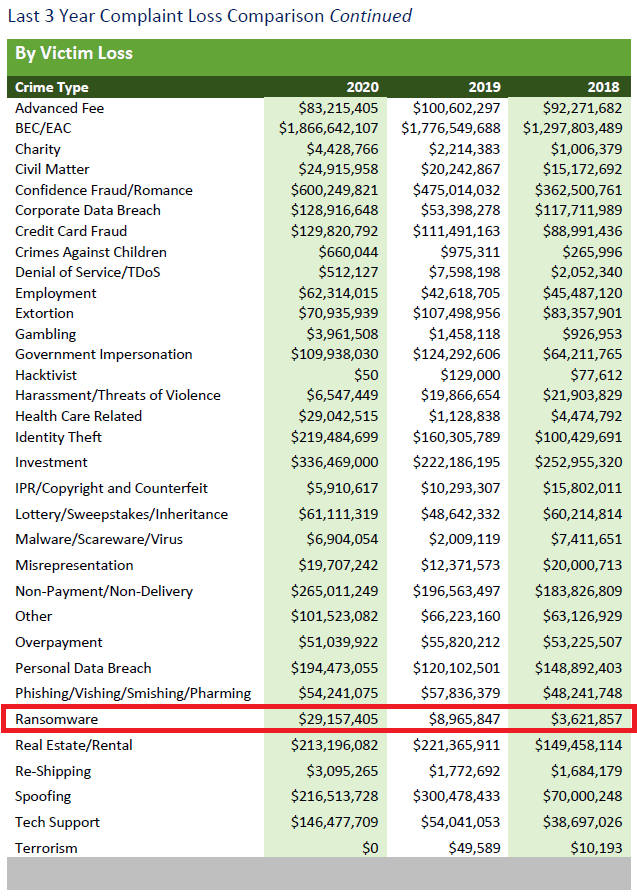

Let’s start by setting out the figures. We will use, primarily, the FBI’s 2020 Internet Crime Report, of which we already made a blog post. According to this report, in the United States alone, “2,474 complaints identified as ransomware with adjusted losses of over $29.1 million” were received. This amount was estimated with a considerable margin of error since the final number does not include dozens of factors that could considerably increase the monetary loss. It does not take into account, for example, the economic loss that involves the extra investment of time, equipment, or additional salaries to those who must decrypt the files (or the insurance payment, if any). It also does not consider cases not reported to the FBI; a widespread practice since companies might prefer to pay for ransomware before it is known that their security system was breached.

If we consider the monetary loss of ransomware over the last three years, it is easy to see the exacerbated increase (see Figure 1). From paying $3,621,857 in 2018, it went on to pay $29,157,405 in 2020. This means a 705% increase in the total loss due to ransomware in three years. Why have ransomware price demands skyrocket that way?

Ransomware and payments: a vicious cycle

Cybercriminals know that ransomware is a profitable activity because there is always someone willing to pay. In this regard, Threatpost published that 41 percent of claims made to cyber insurance corresponded to ransomware attacks during 2020. According to Bloomberg, the cyber insurance company CNA paid $40M at the end of March in response to a ransomware attack. With a single attack, cybercriminals get millions of dollars. That’s a lot more than most midsize businesses would earn in a year. Jennifer Granholm, Secretary from the Department of Energy of the USA, said about it: “Paying ransomware only exacerbates and accelerates this problem. You are encouraging the bad actors when that happens.”

However, if the ransomware is not paid, how can a victim decrypt their files? Indeed, Andre Nogueira, CEO of JBS, and Joseph Blount, CEO of Colonial Pipeline, posed this same question. In the end, both decided that the most immediate solution was to pay the sum requested by the attackers. And these are not isolated cases. Five years ago, IBM did a study in which it concluded that 70% of businesses attacked by ransomware paid, a figure that by 2020 only decreased by 2%, according to Statista.

Of course, all of this results in a vicious circle that can be completed in two steps. First, cybercriminals encrypt information and demand money to unlock it. Second, insurance pays those demands to release the information. Recently, however, cybercriminals noticed a way to demand money in addition to asking for the decryption of information: blackmail. Cybercriminals realized that they are successful in asking for money to prevent them from leaking and publishing that information. Criminals play with companies’ operations, their reputation and, more worryingly, with legal issues. Therefore, companies that work with sensitive information are often the most affected in this regard. Hence, organizations working in the education sector or government entities (which manage a lot of sensitive data) have been two of the top targets of ransomware during 2021, according to the Cloudwards portal.

The list goes on and on

Added to all these series of unfortunate events, with the arrival of cryptocurrencies, criminals solved the problem they had with laundering money. In an interview with the ZDNet’s senior reporter, Danny Palmer, the Chief Digital Officer of Mars Incorporated, Sandeep Dadlani argued that criminals didn’t know how to withdraw the money they charged without raising suspicions. Now that the system is decentralized, it is not possible to see where that money is going. The involvement of cyber insurance companies had aggravated the problem. Before, a criminal could only demand what a person could afford for decrypting their data. There was no point in charging more. Now, they go for the big companies because they know that behind them is an insurance company backing them financially. This same point is made by the RUSI report: “[…] when an organisation has a cyber insurance policy, it might be able to claim the ransom back, which may encourage payment.”

The problem is accentuated to the extent that it would be cheaper to pay the ransom than to regain the trust of customers and investors. If data were to be leaked, the company’s reputation would be severely damaged. Suppose the monetary and reputational convenience of paying the ransom is added to the urgency of certain organizations to resume their services. In that case, you get a cocktail that should be taken quickly and almost without hesitation. Security Intelligence already pointed it out: “agencies that are responsible for upholding a nation’s critical infrastructure […] can’t afford to suffer a prolonged disruption.” This happens with companies in the health, transport, or food sector. It was the case of, for example, Colonial Pipeline and JBS.

Not today!

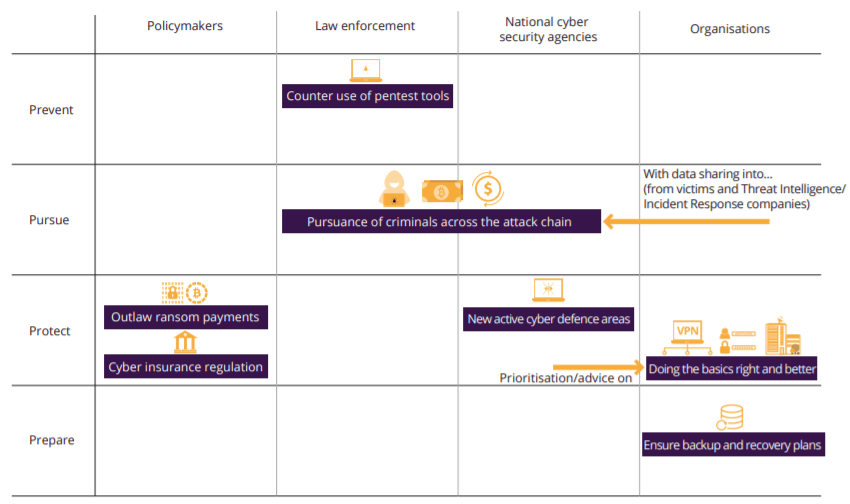

We come back to the question we had already asked. If we all know that paying for ransomware is financing these criminal groups, what should we do? Joshua Motta, CEO of Coalition, a USA cyber insurance company, gives us some insights that his own company always puts into practice. They demand compliance with specific prevention criteria by the companies that request their services. “In order to qualify for insurance, you shouldn’t be doing the types of things that are going to make you a target of a criminal actor,” says the CEO. To do so, the insurance company itself trains its potential clients to strengthen their prevention practices. This may seem weird for an insurance company. It is not common for car insurance, for example, to teach how to drive to their potential customers before agreeing to concluding the deal.

We at Fluid Attacks believe this is the right path to take. Enough of keep thinking that my company will not be attacked! The best way to stop cyberattackers is not to give them the option to attack. In other words, we must be prepared. Prevent ransomware attacks is the best way to avoid them. We must not leave so many things to chance: on the contrary, we must integrate a robust security system from the outset of our software development. The infrastructure must be constantly and continuously tested. Stopping ransomware is everyone’s responsibility. Avoid crying over spilled milk; instead, prepare yourself never to spill it.

The original content can be checked here.

MI Group has partnered with Fluid Attacks to provide services that contribute to the problems and recommendations discussed in this post.